The ten blue links are long passed. So are the average click-through rates (CTRs) for each position.

At first, people would search on their beige boxes and click on the first links. It was the 1990s and we were just beginning to search on the internet for information and things.

Then, the 2000s came, and while Google was evolving, including ads and page rankings, phones were becoming smart, while negotiating the viewport surface and their functions.

In 2012, Google’s Knowledge Graph was born. In 2016, the search engine introduced 3 more Ads slots.

It’s 2020 and the way search looks has dramatically gotten more sophisticated — people search on multiple devices, voice search is on the rise, and as for Google’s SERP features, we’ve reached around 600 different combinations of them, based on queries and desktop/mobile variations.

In the current landscape, this means very different CTRs for the same rank depending on what SERP features are present.

That’s the main issue pixel-based rankings targets to solve.

What’s the hypothesis behind pixel-based rank tracking?

In full, the idea behind the pixel-based rank tracking is the need for accurate measurement of the SEO performance while taking into account the variations of SERP features.

This method proposes to measure in pixels the physical position of a website listing on desktop and mobile devices in order to be correlated with the number of clicks and the visibility that website can get.

Let’s see what this entails in practice, with a couple of questions and examples:

1. Is “1500px” good or bad for my website?

Hundreds and thousands of pixels don’t translate to anything concrete for the brain. What can your client understand when you tell them their website is 1500px below the fold line? And what does it mean for your next steps in improving the organic performance?

The simple explanation could be — the more thousands of pixels, the worse for the website’s positioning. Yet, this measurement doesn’t necessarily paint a clear picture for now.

2. What does “1500px” mean on mobile versus desktop?

As SERPs are not identical and vary a lot, even on the same keyword, based on device, instead of solving the problem of accuracy, you introduce even more complexity in defining what 1500px on desktop and 700px on mobile highlight for a business. Or even what 1500px on desktop would mean for mobile? Is it the equivalent of 4200px? Or not?

Unlike the traditional organic position, there’s not one single meaning — another issue when deciding what’s next.

3. Can I still rank better or did I hit the ceiling on this one?

If we measure ranks based on pixels, then does a certain number of pixels mean a better or worse SEO performance?

Let’s take “fantasy books” for instance. When measuring positions, if you reached rank #1, you knew that your job was done, and you couldn’t improve your performance on that keyword anymore.

But with pixels, each keyword has a different top position height. So you never know if you can move on to other keywords, because your “fantasy books” one is already performing at its best.

4. The Deal Breaker

If the complexity introduced so far may be tackled, here are the situations where the pixel-based rank tracking fails to deliver.

Let’s take a look at “weather”. A search for weather will give you all the answers you need with the Google feature, so there’s no need to go further. On mobile, there are even ads before the weather SERP, so even if your website ranks first, it won’t see any traffic — although the pixel measurement may look good at around 200-300px for your website position. This is pretty straightforward and a decent example to show that the height in pixels for the first organic result is not correlated with the effect the SERP feature has on organic performance.

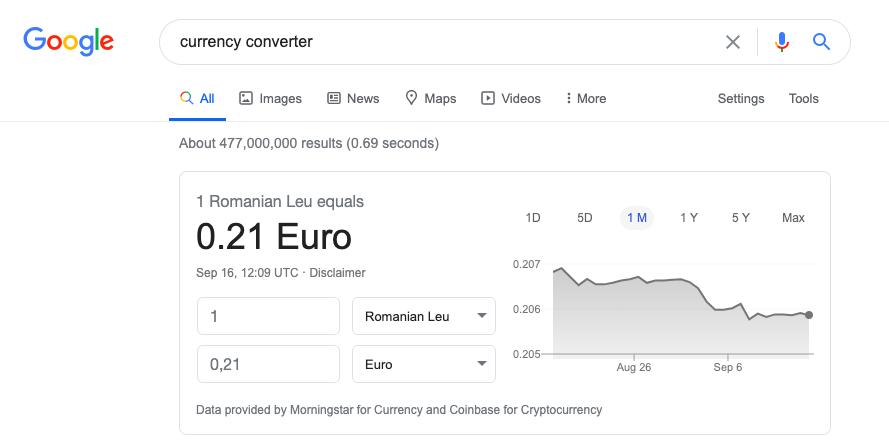

The same goes for searches like “currency converter” or “time in Paris”, which generate an instant answer in the Google SERP.

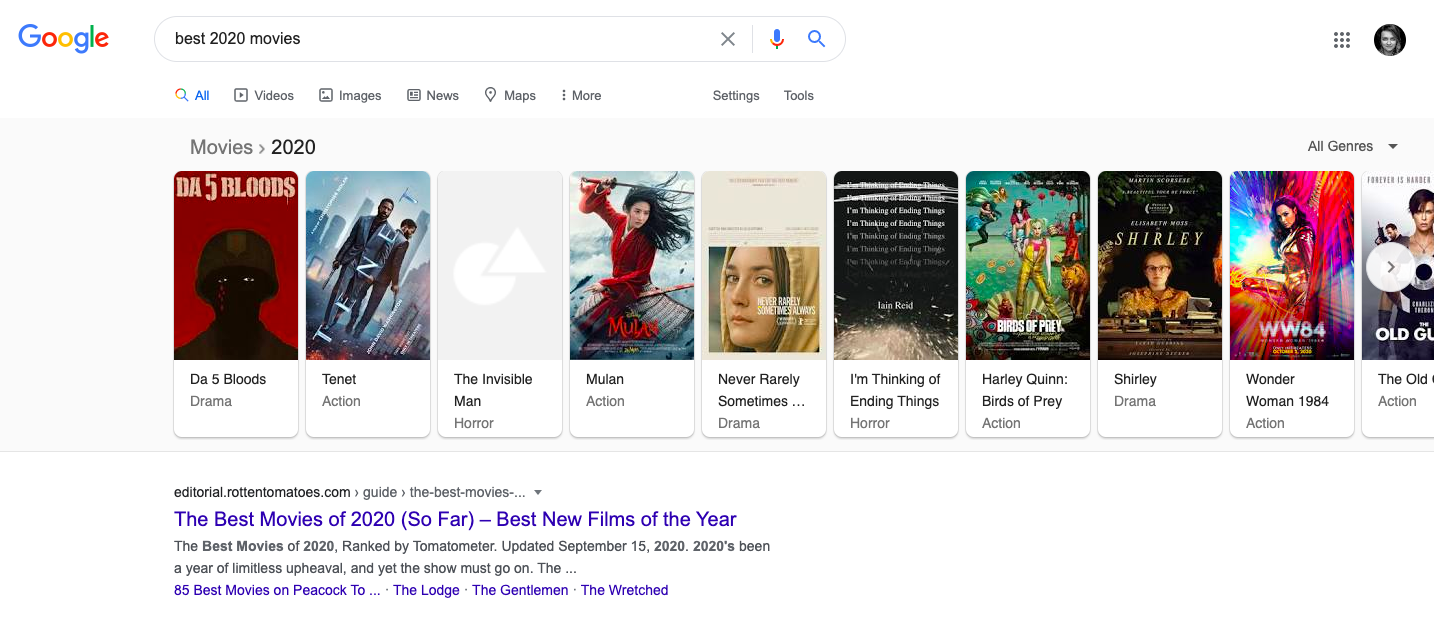

Let’s take another situation — searching for “best 2020 movies” on Google triggers the carousel SERP feature, that shows movie cards before the first organic result.

In pixels, that means the first organic position is again at around 200-300px — that’s pretty good, right? Does that mean there’s no better ranking? You could draw that conclusion based on pixel ranking alone. Yet, the user can explore the carousel seamlessly without ever scrolling to the first organic result and clicking on that.

These examples may be an extreme of our problem, but they already show the cracks in the pixel-based ranking hypothesis.

Let’s look at it the other way around — a person searching for a specific result like “recommended lawyers in Paris”. When hitting enter on Google, there will be a mix of 4 ads, local results (maps), a featured snippet or “People also asked” widget, which take over 3000px, so around 3 scrolls on desktop.

However, the first organic result gets a higher CTR than the previous ads and widgets, even if in pixels it ranks way lower (+3000px below the fold). And that’s because when looking for recommendations of lawyers in Paris, that person won’t look for sponsored ads or search for lawyer offices in Paris. She’s looking for reviews. And that research probably won’t even stop after clicking on the first organic result, but scrolling and clicking even further.

This example again invalidates the pixel-based rank tracking system, which only measures the physical website position related to proximity.

So it’s not only inaccurate, but it becomes misleading and proves the whole theory wrong.

And the problem still remains. What part of the clicks end up on organic results?

What if we could measure just the keywords’ search volumes that generate clicks on organic results?

*We’d solve the SERP features problem and the old rankings would be relevant again:

If pixels are misleading, why not frame the real problem from a different angle instead of trying to create a new “truth” for rankings — how are the CTRs of the first-page organic results affected by the SERP features mix on each device? In other words, what amount of a keyword’s search volume would end up with a click on an organic result?

That way, we don’t care about what SERP features are there when looking at keyword rankings. If we have a keyword that is searched 100k times per month, but only 10% of those searches end up with a click on an organic result, then from an SEO point of view, the keyword has only 10k searches per month. And that’s fine, because now we know what we’re going after when choosing the keywords we’ll focus on.

With that adjusted search volume metric, tracking the keyword position is the best keyword performance metric we can find. It’s simple, intuitive and correlated with the results the keyword will generate.

After all, it’s the link between CTRs and business outcomes that is relevant for your SEO client, that’s where the value is.

At SEOmonitor, we wanted to get to the bottom of this and understand how SEO performance and business results are affected. So we ventured into thorough research to determine how the CTRs of the top 10 positions are influenced by those 600+ SERP features. You can find the whole analysis and data sources in our article here.

The result was a CTR curve for the first page organic results on each combination of SERPs and each device.

With that data, we can now sum up the CTRs of the organic results for each mix of SERP features, so we can estimate the % of search volume that ends up clicking on that organic result. That way we’ll estimate the new search volume for a keyword. We’ll let our users access the total search volume for reference.

This research with its solution helped us already optimize our Forecasting module, highlighting the additional visits you can generate once a specific visibility improvement is achieved, which is calculated using device- and SERP-based CTRs.